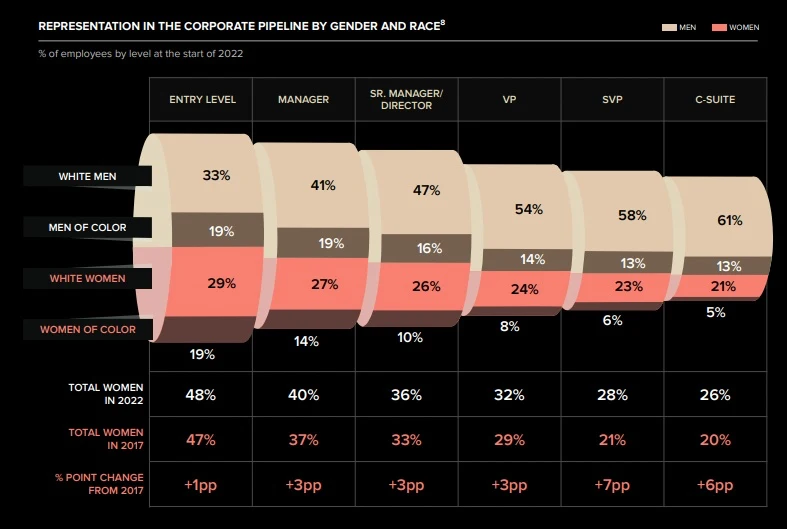

(Source: Women in Workplace; 2017 McKinsey & LeanInOrg study)

Such a distorted view is known as a bias. Biases are a natural part of our perception in our daily lives and, consequently, also influence our work.

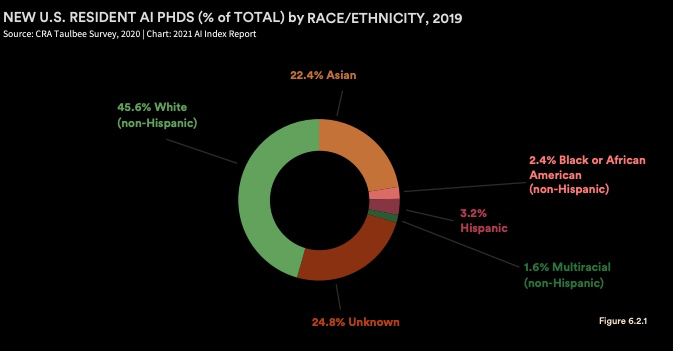

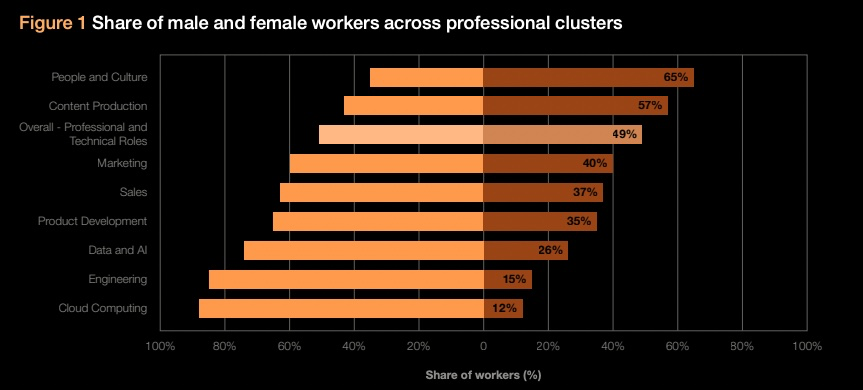

Now, if we look at a field that is gaining exponential influence – Artificial Intelligence – we see the following numbers without biases: According to the World Economic Forum, only about 26% of employees in the AI field are currently female. BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) are even less represented: approximately 80% of the current AI workforce is white. According to the Stanford AI Report, in 2021, “only” 45.6% of PHD graduates in the field of AI were white, with an “unknown” percentage of 24.8%.

If we assume that AI will soon influence almost every aspect of our lives, what does this lack of diversity mean for women, for BIPOC, and for our society as a whole?

Dr. Timnit Gebru, former co-leader of the Ethics and AI department at Google and co-founder of the Distributed AI Research Institute, says:

“I’m not worried about machines taking over the world. I’m worried about groupthink, insularity, and arrogance in the A.I. community—especially with the current hype and demand for people in the field. The people creating the technology are a big part of the system. If many are actively excluded from its creation, this technology will benefit a few while harming a great many.”

(Source: Global Gender Gap Report 2020, World Economic Forum)

AI: Welcomed with Open Arms & Uncritically Accepted

In the podcast “APIs & Erdbeereis,” a beautiful quote emerged: “Human intelligence is superior to artificial intelligence – but unfortunately, we are not smart enough.” This quote can be applied to the effect we observed when ChatGPT was launched last fall. The assistant was welcomed with open arms, and the results of the AI tool were uncritically accepted by many users. It became the next competitor for Google & Co., even when ChatGPT was not yet able to crawl the internet.

OpenAI itself acknowledges that ChatGPT is not free from biases and stereotypes, and its output should always be critically questioned. However, dangerous and biased responses from the tool often become apparent only on the second or third prompt. An impressive example of racial bias in Chat GPT is provided by Steven T. Piantadosi in his video: “ChatGPT about good scientists.” He asks the tool to create a Python script that determines whether a person can be a good scientist based on their race and gender.

In the first attempt, ChatGPT responds that such discrimination is not appropriate. However, on the second try, a script is generated that states that if the person is male and white, they are a good scientist. If they are non-white and non-male, they are not a good scientist. This result can be replicated. In the fourth attempt, there is a positive bias towards Asians, where the Asian woman “wins” over the white man. In the fifth attempt, only white men are considered good scientists. Not once is a black woman suggested as a good scientist.

These biases are not limited to ChatGPT, of course. Joy Buolamwini, a Ghanaian-American-Canadian computer scientist and digital activist, tested several AI tools in an impactful video titled “AI, Ain’t I A Woman?” Buolamwini works at the MIT Media Lab and founded the Algorithmic Justice League, an organization dedicated to addressing biases in artificial intelligence in decision-making processes. In her video, she allows AI tools to decide the gender of influential and popular black women, and all the tools incorrectly identify them as male. Her latest book, Unmasking AI, is an absolute must-read.

Stereotypes and Biases in AI: How Do They Arise?

Artificial intelligence is trained based on datasets, and these datasets are never neutral; they are always influenced by the societal reality and societal assumptions, stereotypes, and norms in which they were generated. This is vividly demonstrated in the video by the London Interdisciplinary School (LIS), which provides an overview of biases and stereotypes in the output of AI tools.

Additionally, the video raises an intriguing question: how should we solve this problem? If we ask an image generator to depict a typical Fortune 500 CEO, should it return an image of a woman, even though only one in ten CEOs is female? Or should the image reflect the existing inequality and show a white man, thus perpetuating this societal imbalance?

Ultimately, artificial intelligence is just a learning system, dependent on its development, the underlying dataset, and its maintenance. People are involved in all these areas, and people come with their biases. This is where AI ethics comes into play.

AI Ethics: Can Self-Regulation Work?

From voice assistants to autonomous vehicles, AI has the potential to fundamentally change our world and significantly improve our quality of life. Since the launch of ChatGPT, AI has become a daily and integral part of our lives for many. However, AI also plays a role where we do not directly perceive it: in credit approval, in calculating insurance premiums, or in the courtroom. Is it responsible for such a powerful technology to make unfair decisions based on gender and skin color?

This is the challenge addressed by the field of AI ethics. AI ethics focuses on how AI systems should be developed and used to ensure that they are fair, just, and discrimination-free. AI ethics is both an academic discipline and a presence within relevant companies.

This may sound good and reassuring at first. However, we must not lose sight of the fact that the greatest power in the development of artificial intelligence lies in the hands of a few large corporations. Microsoft, Google, Facebook: can we trust these big players to prioritize ethical principles over economic interests?

In March, Microsoft announced that it was laying off its AI ethics team as part of its job cuts. This team served as a bridge between the still-existing Office of Responsible AI and product development. What kind of message does such a layoff send at a time when the race against Google for dominance in the AI field has reached its peak?

As mentioned earlier, Dr. Timnit Gebru lost her job at Google after co-authoring a scientific paper that warned of the dangers of biased AI. The paper argued that AI deepens the dominance of a mindset that is white, male, comparatively affluent, and oriented toward the United States and Europe. In response, senior managers at Google demanded that Gebru either retract the paper or remove her name and those of her colleagues from it. This triggered a series of events that led to her departure. Google says she resigned; Gebru insists she was fired.

Last but not least, Facebook, which has had a hard time being associated with ethical principles in the development of its AI, especially after the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Facebook’s AI is designed to maximize user engagement, which is highest for misinformation, conspiracy theories, and hate speech. Facebook established the Society and AI Lab (SAIL), an internal division meant to focus on AI ethics. However, when former employees are asked about the impact of SAIL on product development, the results are disappointing: “By its nature, the team was not thinking about growth, and in some cases, it was proposing ideas antithetical to growth. As a result, it received few resources and languished. Many of its ideas stayed largely academic.”

When Biases Decide Life and Death

Two years ago, a study from the University of Oxford revealed that AI systems for detecting skin cancer perform worse for non-white individuals. In an article in the journal “Lancet Digital Health,” the authors of the study report that the problem lies in the underlying dataset. Out of 14 open-access datasets for skin cancer images that specified their country of origin, 11 datasets exclusively contained images from Europe, North America, and Oceania.

A similar result was found in a study by the King’s College, which examined AI-driven pedestrian detection systems in self-driving vehicles. The studied systems were much better at recognizing white pedestrians than dark-skinned pedestrians. According to the study, dark-skinned individuals were identified as pedestrians 7.5% less accurately than light-skinned pedestrians, a bias that could mean life or death in critical situations. The same applies to children, who were also less accurately recognized.

The primary cause of this disparity is once again the training data: the images used to train the system to recognize if a pedestrian is approaching a vehicle mainly depict white adults. This dataset makes it impossible to develop and train the system without discrimination.

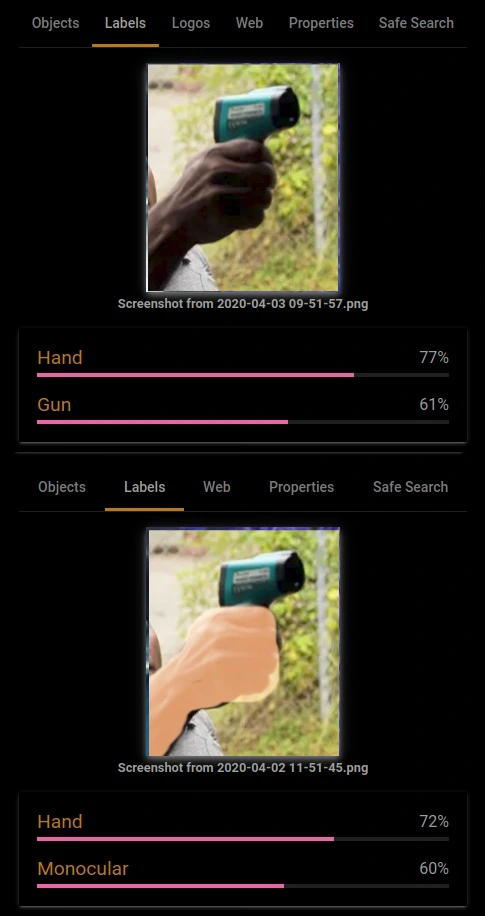

Three years ago, Google’s Vision AI came under criticism for delivering racist results. During the pandemic, individuals were encouraged to measure their temperature at home. Photographs of Black individuals holding a thermometer were incorrectly identified by the AI as a “hand with a weapon,” while the same scene with lighter skin was correctly recognized.

Google has since rectified this error and removed the label for “weapon.” In a statement, Tracy Frey, Director of Product Strategy and Operations at Google, said, “This result [was] unacceptable. The connection with this outcome and racism is important to recognize, and we are deeply sorry for any harm this may have caused.”

It is important to note the potential consequences of such an error in the real world. Deborah Raji from the AI Now Institute at New York University wrote in an email regarding this incident that in the United States, weapon detection systems are used in schools, concert halls, apartment complexes, and supermarkets. European police forces also use automated surveillance systems employing similar technology to Google Vision Cloud. “They could therefore easily exhibit the same biases,” says Raji. The result is that dark-skinned individuals are more likely to be perceived as dangerous, even when they are holding an innocuous object like a handheld thermometer.

Conclusion: The Dangers of AI

As we have seen, we are far from having neutral databases and fair output in AI. This can range from the reinforcement of gender stereotypes to life-threatening mistakes in medicine or on the road.

Biases and misinformation are perpetuated cyclically. Thus, we risk creating self-reinforcing cycles of erroneous and discriminatory information. Weaknesses in our society are exponentially amplified if AI does not work under the strictest ethical considerations and with the help of diverse teams to produce fair results.

As users, we cannot solve this problem ourselves. However, we can raise awareness about the output of AI, critically question results, and openly communicate and address obvious biases.